Your cart is currently empty!

Tag: startups

Evaluating Ed Tech Efficacy Through a Wider Lens

Image: “‘STEM Boys Night In’ at NASA Goddard”, CC BY 2.0

I’m an avid reader of Ryan Craig’s Gap Letter, a bi-weekly newsletter that analyzes key challenges in education seasoned with poignant cultural references. His latest newsletter, Research Universities Love Research… Except When It Involves Student Learning, addresses one of the thornier issues in ed tech: efficacy research.

While I broadly agree with Ryan’s observations and conclusions, it’s worth pointing out that efficacy research on ed tech is less black and white than we may want to believe.

By ed tech, I mean any technology tool or digital content that is used to support educational processes — usually teaching and learning specifically.

By efficacy, I mean how well the ed tech tool does what it promises to do, either explicitly or implicitly.

Here are some promises that an ed tech may make:

- Improved student learning outcomes

- Higher retention and/or graduation rates

- Better student preparedness for college or career

- Higher levels of student engagement

- Lower levels of student personal problems (e.g. financial, behavioral, mental, etc)

- Broader or deeper learning experiences

- Increased teacher or learner autonomy or agency

The first 3-4 promises in the above list are probably top of mind when one thinks about researching the efficacy of ed tech. But there are other valuable promises that ed techs might make, for instance:

- Time-savings, for students, teachers, or administrators

- Lower costs, for students or institutions

- Greater flexibility in instructional practices or content

- Increased access to education

- Reduced pain, stress, or extraneous cognitive load, for students, teachers, or administrators

Though these latter benefits relate more to the “business” of education, they are legitimate benefits nonetheless. A technology that addresses the process of education but not the outcomes of education is still educational technology, though its “efficacy” may need to be measured differently.

The idea that some ed tech is designed primarily to facilitate educational processes takes us toward an important realization:

The impact of any educational technology is co-determined by how it is used.

One of the lessons of educational technology that I brought to Instructure’s first Research and Education team was that technology does not improve anything by itself; people do. People can leverage technology to improve access to education, or student engagement, or learning outcomes, and some technology is better suited for these purposes than others, but any kind of change begins and ends with people.

In other words, you can lead a horse to water but you can’t make it drink.

This is especially true in higher education, where the proverbial horses (no offense!) may be instructors (who claim academic freedom to drink or not drink) or students (who are adults under no compulsion to succeed) or administrators (who have plenty of other responsibilities to keep them busy).

And while all ed tech will show some opinion about how it should be used, some ed tech products will purposely be open to a wide variety of uses, while others will exert their opinion more forcefully.

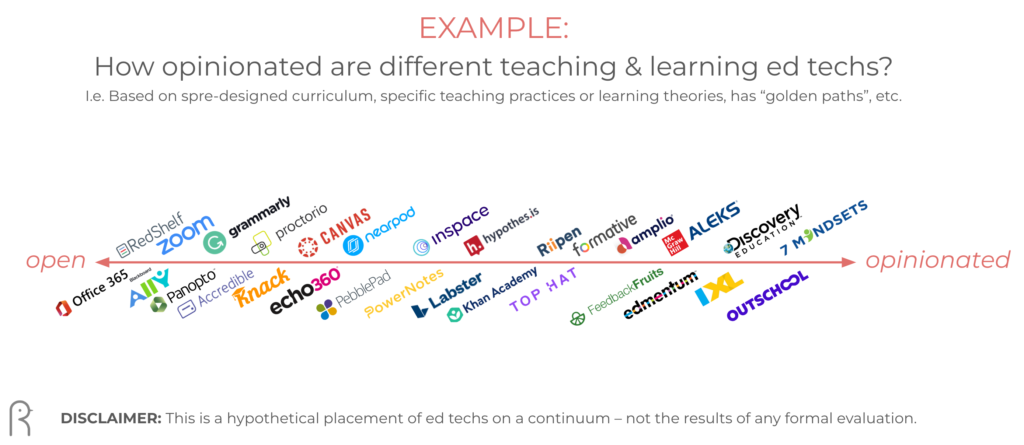

A continuum between “open” and “opinionated” may be helpful here, where an ed tech product may be deemed more open to various uses versus limiting variations in use based on the “opinion” of the product designer.

I should probably note that “opinionated” is not meant to be a pejorative here, but I didn’t want to use “bias” either as that tends to steer product designers in a different direction than what I intend. If you have a better term, let me know in the comments.

For example, let’s say we are interested specifically in ed tech products that may influence student outcomes such as learning or engagement – i.e. teaching and learning tools or content.

On the one end of this continuum we’d find products that are wide open to a variety of instructional uses based on the preferences and opinions of the user. Microsoft Office 365 seems like an obvious example, but so would Blackboard Ally, a product created to ensure files are available to learners in a variety of formats to support accessibility.

On the other end of the continuum we’d find products that are created for a single, specific use and reflect strong pedagogical opinions. 7 Mindsets seems like a clear example of a more “opinionated” product, as it provides a complete, out-of-the-box digital curriculum, designed to reflect the company’s beliefs about mindset research and delivered according to their pedagogical position.

Learning Management Systems would fall more toward the “open” side than the “opinionated” side, and teaching tools designed for specific types of learning activities would fall more toward the “opinionated” side.

Here’s a quick, hypothetical example of how a sample of ed tech products might land on such a continuum:

Someone’s going to get upset with how I placed a particular product on this spectrum, which is fine. This is not meant to be precise, it’s merely meant to illustrate a point:

The efficacy of any ed tech product will be heavily influenced by how it is used. And some ed tech products allow a greater variety of uses than others.

This naturally makes those ed tech products harder to evaluate from an efficacy perspective – independent of a specific implementation within a specific context by specific users with specific instructional theories and practices.

That doesn’t mean we can’t evaluate the efficacy of these products; it’s just much harder to do, and much more dependent on a variety of other factors – many of which are difficult to control (especially in higher ed).

But compare that to, for example, out-of-the-box digital curriculum aimed at improving reading comprehension amongst K-6 ELL students. Evaluations of this kind of ed tech are going to be much easier to control. Certainly there will be some of the same confounding variables as one might see in more “open” ed tech (e.g. student demographics, ability levels, and teacher support), but researchers wouldn’t have to spend as much time controlling the instructional design or methodology as those will be baked into the product.

This is all to say that we should be careful when we think about ed tech products from the perspective of efficacy; not all ed tech products can be easily evaluated, and many ed tech products are actually designed to allow for a broad range of uses, in this case instructional practices and philosophies.

When we do judge the efficacy of ed tech products, we must do so in context of the problem they are trying to solve, and not conflate their purpose with other ed tech products with different problems to solve.

And, frankly, sometimes the efficacy of an ed tech product is obvious without research, even though it could be measured. This is more often true for products that make “business” promises, such as time-savings or access.

Let’s go back to Blackboard Ally as an example: It’s obvious that, in order to learn/achieve, students need to be able to access the learning resources provided for them. But some students (e.g. students who are deaf or hard of hearing) can not learn from those resources due to the form they were created in (e.g. a video). Therefore, providing those resources in an alternative form that is accessible to all students is beneficial. I don’t need efficacy research to prove the value.

But I will need to know that the product is easy to use and integrates well with other systems, like the LMS.

I think this is partly why some higher ed decision-makers put so much weight on ed tech characteristics that aren’t directly related to educational efficacy, as Ryan Craig points out in Gap Letter:

When a recent survey asked over 300 universities about the most important attributes for making edtech purchasing decisions … , here’s what mattered, in order of priority: 1. Ease of use; 2. Price; 3. Features; 4. Services; 5. Sophistication of AI; 6. Evidence of outcomes

Another factor is surely that those higher ed decision-makers tend to favor more “open” ed tech products, knowing that each instructor or faculty member has academic freedom.

Which leads us to an elephantine question: Should higher ed be more doctrinaire in terms of faculty teaching practices and curriculum?

Perhaps.

Regardless, the reality is, if we look at adopting ed tech as a means of changing educational outcomes, we must first expect to change educational practices.

Some ed tech companies try to bake that change into their product, essentially requiring any users who might adopt their product to change their practices. Change is hard, of course, and no one wants to be forced to do something they’ve always done in a different way unless they absolutely have to. I expect that this may be a factor in the startlingly low rates of adoption amongst some ed tech tools. But encouraging users to adapt their practices by providing “golden paths” or other means of encouragement and reward is something I think all ed tech product managers must consider, especially if their product is more opinionated.

Some ed tech companies integrate some kind of change management services or support along with their products throughout its full life-cycle, not just through initial implementation (Ryan mentioned Mainstay; I’ll add Feedback Fruits as another ed tech that seems to do a good job of this). A change management partnership approach such as this certainly requires greater commitment and more resources on both sides. But it also holds the greatest promise for ed tech companies to be able to affect positive change within educational institutions, and thereby secure their value with decision-makers.

This kind of approach should also create natural opportunities for efficacy research. If practiced broadly, it should also result in a wider variety of organizational contexts from which to draw on as examples or models for similar institutions.

No matter the approach, I believe progress in efficacy research depends on ed techs and educators working together to define a better way forward:

- Every ed tech must get real about the actual outcomes that their product is designed to deliver (and it’s not always “improve learning”). They must then decide how to measure that from customer to customer in a way that legitimizes their effort, and isn’t simply an empty gesture for marketing points.

- Every ed tech customer should recognize that this effort is impossible without them, and thus part of the “cost” of adopting an ed tech should be to have staff time, data, and perhaps even researchers available to contribute.

4 Mind-Shifts for Startup Founders Who Fear Being Salesy

Business people shaking hands in agreement” – RawPixel on Flickr – CC BY Sales are, of course, critical for any startup. Especially for early-stage startups, it’s up to the founder(s) to determine product-market fit and map a sales strategy through, what else? Selling.

But founders aren’t always comfortable selling assertively. They may have their own negative perception of sales people, and thus are reluctant to come off as “sales-y”. Founders may also be so personally invested in their product/solution that they may have developed a fixed mindset as a defense mechanism against criticism or flaws, which disinclines them to be an a position where they might face rejection.

Founders of ed tech startups may have additional reasons to have concerns about selling assertively. Oftentimes they are pitching to highly educated individuals who are trained to thinking critically and analytically. These are people who purposefully embraced the mission of a non-profit organization, and may approach any corporate offering with significant skepticism.

But it is possible to sell assertively and authentically, even for founders who aren’t naturally comfortable doing so. Here are 4 suggestions for startup founders who personally struggle with internal feelings arising from selling:

1. Don’t focus on the customer’s perception of you (i.e. as sales-y), focus on your passion for helping the customer solve a problem. Authenticity owns perception.

2. Don’t focus on your product or company at all (at first), focus on the customer. A legitimate understanding of the customer’s problems in their context should naturally lead to your solution. If it doesn’t, take note* and move on.

3. Don’t be self-conscious about imperfections in your solution: Many weaknesses in your product/solution can only be addressed through the learnings you will glean from customer adoption. (It’s OK for customers to understand this, too.)

4. Don’t be shy about driving a deal to close: The only way you can help your customer is if they choose to formally adopt your solution. The sooner they adopt, the sooner you can make a positive impact on (at least one corner of) the world.

As someone who is a chronic self-doubter and has always been reticent of coming off as sales-y, I’ve applied these 4 ideas until they have become habits. Over time, habits trump inclinations, and you’ll find yourself increasingly comfortable assertively selling.

Those are just my ideas. What about you?

Are you self-conscious about sales? If so will these suggestions help?

Or perhaps you were once self-conscious but aren’t any more. If so, what caused you to change?

Maybe you’ve never been self-conscious about sales. What mindset do you hold that makes selling straight-forward?

*Repeated rejection should be examined, as it may mean you’re doing a poor job engaging with customers and representing the value, or your product/solution is a poor fit for the target customers’ needs. In either case, a pivot may be in order — in your methodology, your segment strategy, or your product strategy.